Sometimes a journalist goes out in search of one story, and comes back with another one that’s altogether different and worlds better. That happened to me five or six years ago, when I rode from Kansas City to Greenwood, Missouri to interview an old guy named Mike Harper, who had one of the world's largest inventories of old Moto Guzzi V-twin parts.

By the time I met Mike, he was in his mid-70s and had pretty much turned over the day-to-day operations of Harper’s Moto Guzzi to his son, Curtis. That left Mike free to take me on a long ramble through barns and outbuildings that contained an impressive collection of motorcycles and countless new-old-stock Guzzi parts that he’d amassed by buying up the inventories of about 130 dealerships as they dropped the Guzzi brand or just went out of business.

It was a cool story. The barns were photogenic. I had another column in the bag by the time we’d worked our way back to his office.

But as we reached the office door, several nice racing trophies caught my eye. My curiosity was really piqued when I leaned in and saw that they were engraved in Japanese. Mike casually told me that in the early 1960s, he’d raced for the Lilac factory team in the Japanese championship.

I have to say, dear reader, that over the course of my career I’ve encountered a few old ex-racers who exaggerated their deeds. There’s a reason they print T-shirts that say, “The older I get, the faster I was.” That’s why they also say, “Pictures or it didn’t happen.”

So I asked: Did he have photos? By then he’d sat back down and wasn’t about to get up. He called over to his wife, who dug out a cardboard box full of old black-and-white snapshots.

“Here’s me on a Honda RC160,” he said. Then, absent-mindedly, he mentioned that Soichiro Honda had given him a Honda cufflink and tie-tac set; now where was it?

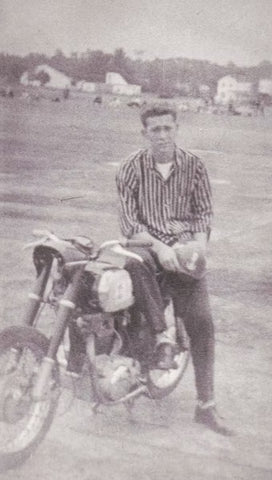

I realized I had to come back and start over, on the real story. A few days later I returned with a small scanner. I sat down across from him at his desk and we went through scores of evocative old photos. They showed a thinner, younger, faster guy but it was unmistakably Mike — including a shot of him straddling a Honda RC160 factory racer, surrounded by engineers and race-team mechanics at Honda’s Hamamatsu test track. Out of frame but there that day: Soichiro Honda.

Racing in Japan as the Japanese motorcycle industry came of age

Here’s how it happened: After a couple of years racing scrambles, flat track, and the occasional road race in the Midwest, Mike enlisted in the U.S. Navy. They trained him as a helicopter mechanic and shipped him out to Atsugi Naval Air Facility, about 20 miles from Tokyo. That was in 1959.

Just outside the main gate of the base, the town of Sagami Otsuka was “A train station, 45 bars, and a police station,” Mike recalled. The bars plied sailors with beer and young women. Mike gave me a sly look, noting that they were “government-inspected.” (Yeah, it was a different time.)

To make matters even better for an 18-year-old from the Midwest, there were motorcycles everywhere. He quickly bought a single-cylinder 350 cc Honda Dream from a sailor who'd “gotten orders” — meaning, he was getting shipped back stateside. Then he bought a BSA Super Rocket.

Within a few months, the Navy transferred all the base's helicopters somewhere else, leaving Mike without a job. He was reassigned to Shore Patrol — the Navy's version of military police. It was a cushy assignment that left him with lots of free time.

Although the Navy didn't allow racing on its bases, there were several Air Force bases nearby where, as Mike said, “They let them get away with anything. They’d block streets for drag races. They made a motocross track right on the base at Yokota.”

Mike found himself racing more often in the service than he had as a civilian — drags, scrambles, even road races on courses laid out on USAF runways and taxiways.

He joined the Atsugi Road Brothers, whose members were American sailors from the base and Japanese bikers from the nearby towns. The Navy was definitely not a total killjoy. It let them hold meetings on the base and even let them use Navy trucks as race transporters. When the Americans were off-duty and the Japanese were off work, they hung out in front of Aoki Motors, a Honda and Yamaha dealership in Yamato, just beyond the naval station's east gate.

At first, he was limited by the mechanics' broken English and his own impromptu sign language, but the shop's mama-san — the owner's wife — gradually taught him enough Japanese to buy food or gasoline and find his way around.

"I learned enough to get into trouble," Mike said without providing details; his wife was across the room.

If they weren't racing, they "boondocked" — explored the network of tiny roads and footpaths in the hilly countryside.

Through the Road Brothers, Mike was able to get a Japanese racing license. One of the biggest meetings of the year was Fujinomiya, a scrambles held near Mount Fuji. In 1959, Japanese racers rode their Honda CB92s, or Yamaha YDS models, no matter what the course. John Surtees and Geoff Duke made an appearance and took a brace of Yams out for a demonstration lap. Mike's BSA was a handful on the rough course.

"There was a club from Tokyo, it was either called the Crazy Brothers or Crazy Riders," he told me. "They all had YDS Yamahas with open shorty chambers and they'd get right on your ass. You couldn't hear yourself think. They were hard to get ahead of, cause they'd gang up on you."

Mike's friend, Tomiyo Aosabi, worked at a laundry; he used a 250 cc Lilac to make deliveries. The dealer who sold "Tommy" that bike ran Lilac's race team and heard stories of the Yankee's race prowess.

"I was not the Geoffrey Duke of Japan," Mike admitted. "I just had a bigger bike than most of ’em and was nuttier than most of ’em."

Whatever. The Lilac team manager recruited him for a few races, including the next year's Fujinomiya. Lilac was a quaint name for a motorcycle and their metallurgy was quaint, too; at least, too quaint for a 180-pound rider with a win-or-crash attitude.

One of the biggest road races was held on closed roads from Chiba to Atami. The course made a big loop around Tokyo, 100 miles or more on tarmac and gravel roads. Balcom BSA was the official dealer in Tokyo; they tuned Mike's A58 for the event. He was leading by the time he reached the longest straightaway, along a beach road.

"I heard a bike coming up behind me. It sounded like an air raid siren," Mike recalled. "I was doing about 115 and he was still shifting."

That was his first encounter with the Honda RC160. That early version of the famed 250 cc four-cylinder was fast, but Mike outraced it in the hills and towns. "It was too wide and too low," he recalled. "No one had enough body english to make it corner."

A few high-profile race wins got him an invitation to join the Tokyo Otokichi Club, whose members were wealthy and connected motorsports fans. He was invited to Hamamatsu, where he met Soichiro Honda, and tried the RC160 for himself on Honda's test track.

"I never wanted to leave [Japan]. By then, I'd already extended once," Mike said. "But I must've pissed somebody off, because I got orders" to ship out back to the states.

How did he feel about leaving, I wondered?

"There weren't any big, teary good-byes," he told me gruffly, "but we had a couple or three going-away parties." He sold his bikes and left most of his trophies with Mama-san at Aoki Motors. Even though he later became a Yamaha dealer himself, he never returned to Japan or saw any of his Japanese "road brothers" again.

As I packed up my voice recorder and scanner, I asked him if he had realized, back then, that he was seeing motorcycle history being written.

"Nah!" he scoffed. "I was a wild kid. I was too busy looking for trouble."

Did he have any regrets?

"Honda CB92s were $315 brand new. Now, even a shitty one's worth $10,000. I bet I raced and crashed a million dollars’ worth of ’em," he told me, ruefully. "I wish I'd kept even one."

Coda

I’ve interviewed scores of ex-racers and written as many racing stories. But Mike Harper’s stuck in my mind. For its sheer serendipity; if I hadn’t noticed his trophies, he might not have mentioned his Japanese history at all. For how friendly the Japanese were, hosting Americans who 15 years earlier had been implacable foes; could that even happen now? And for how quickly a naive kid from the Midwest bridged that cultural gap, thanks to motorcycles.

A few years ago, Mike auctioned off most of his eclectic collection. I guessed the auction was prompted by health concerns. I had occasion to call Harper’s Moto Guzzi a few weeks ago and when Mike’s son Curtis answered the phone, I was a bit hesitant to ask after his dad, afraid what I might hear.

As I feared, Mike is doing poorly. But Curtis put me through and we chatted for a few minutes. I told him what I’ve just told you. "Man, your story may be the coolest one I’ve had the privilege of writing up."

Mike mainly remembered that I had made a disparaging comment about his weight. I didn’t remember that part; when I tried to find the original story online, I realized it was gone. Eventually, I found my copy of the original text. I’d written, "He’s now three times the age he was when he raced, and about three times the weight." That was hurtful. Age catches up; it just does.

Even more luckily, I was able to find my scans in an old folder on a desktop Mac that’s approaching vintage status.

I’m happy that Common Tread has given Mike’s story and photos another life and that they’re once again available to anyone who cares to click through them.